Key Takeaways

- Preventive is a startup focused on using embryo gene editing to prevent hereditary diseases and has raised around $30 million from high-profile backers, including OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong.

- Heritable human genome editing (using genetically modified embryos to initiate a pregnancy) is effectively prohibited in the United States, the UK, and at least 75 of 96 surveyed countries, forcing any reproductive use of this technology into legal gray zones or less-regulated jurisdictions.

- Alternative researchers and biblical commentators see these investments as a high-tech reboot of eugenics and a possible fulfillment of end-times warnings about the “days of Noah,” while official bodies frame it as cautious, disease-focused research—leaving open questions about where this work will actually happen and who will control it.

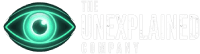

Behind the Glass: Inside the Race to Edit Human Beginnings

Picture a lab deep into the night, lights dimmed except for the glow from microscopes and screens. Embryonic cells float in a Petri dish, their DNA mapped out like code on a terminal. CRISPR tools target specific sites, slicing and rewriting sequences with precision that feels almost too clean. Funds from Silicon Valley pour in, channeling through networks to an unmarked biotech facility somewhere offshore. This isn’t a literal snapshot of Preventive’s operations—it’s a composite to capture the mood: futuristic, sterile, yet laced with unease. What unfolds here could redefine humanity itself.

Preventive operates as a low-profile startup with serious backing, aiming to edit embryos to block hereditary diseases. Tech leaders like Sam Altman of OpenAI and Brian Armstrong of Coinbase have invested. But in places like the US and UK, implanting these edited embryos for pregnancy is off-limits under current rules. That pushes any real application toward international shadows, where regulations thin out. With venture capital driving the pace, these gaps allow experiments that might shift the course of human evolution, far from public eyes.

Why Preventive Has People Talking About a New Eugenics

Observers in alternative research circles, privacy advocates, and faith communities aren’t buying the surface story. They argue embryo gene editing goes beyond stopping diseases—it’s a gateway to selecting traits, much like the old eugenics push for “better babies” at state fairs. Documented facts show Preventive’s funding and the legal barriers to heritable edits. But patterns emerge in discussions: whispers of elite breeding programs disguised as medicine.

These voices connect the dots to America’s eugenics past, where over 30 states enforced sterilization laws, affecting around 60,000 people by the 1940s. They draw lines to Nazi Germany’s racial hygiene efforts, which sterilized more than 400,000 before escalating to worse horrors. Biblical interpreters zero in on Genesis 6, describing corruption of flesh through unnatural unions in Noah’s time, and Jesus’ words in Matthew 24 about end times mirroring those days. For them, modern gene tweaks echo that ancient boundary-crossing.

Online forums buzz with theories that tech moguls will sidestep Western bans by heading to places like Gulf states or Asia, where oversight is looser. The fear? A world where gene-edited kids become the norm through market pressure, not force—creating a subtle eugenics enforced by social expectations. These aren’t wild claims; they’re grounded in historical precedents and current regulatory holes.

Follow the Money, Read the Laws

Let’s get to the verifiable details. Preventive has pulled in about $30 million, with confirmed investors including Sam Altman and Brian Armstrong. The company positions itself as a force against hereditary diseases via embryo editing. But the legal map is clear: no federal ban in the US, yet FDA rules block using edited embryos for pregnancies, and NIH won’t fund heritable changes. The UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act permits research edits under tight controls but forbids reproductive use.

A 2020 global survey of 96 countries reveals at least 75 outright prohibit heritable genome editing, with five allowing limited exceptions. None green-light open reproductive applications. Meanwhile, 11 nations—including the US, UK, and China—permit non-reproductive embryo research with restrictions. Groups like the WHO and the European Convention on Human Rights push for ethics and global standards, but they admit rules aren’t foolproof against future shifts.

This ties back to history. US eugenics in the 1920s–1930s led to forced sterilizations in over 30 states. Nazi Germany, drawing from those ideas, sterilized over 400,000 in the 1930s. Here’s a quick table of key figures:

| Metric | Value | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Preventive Investment | $30 million | Funds raised by the startup for embryo gene editing to prevent diseases | Preventive company announcements and investor reports |

| Countries Prohibiting Heritable Editing | At least 75 out of 96 | Nations with explicit bans on using edited embryos for reproduction | 2020 global survey of genome editing regulations |

| Forced Sterilizations in the US | Around 60,000 | People sterilized under eugenics laws in over 30 states by the 1940s | Historical records from US eugenics archives |

| Forced Sterilizations in Nazi Germany | Over 400,000 | Individuals sterilized under racial hygiene programs in the 1930s | Historical documentation from Holocaust research |

| Countries Allowing Non-Reproductive Embryo Research | At least 11 | Nations permitting controlled research on edited embryos without reproduction | 2020 global survey of genome editing regulations |

Precaution or Power Play? How Institutions and Insiders Frame the Future

Official sources paint a picture of restraint. Regulators and ethicists say heritable editing remains forbidden until science, ethics, and society catch up. They highlight potential to fix genetic disorders, insisting on a divide between healing mutations and chasing enhancements. The WHO calls for caution and collaboration, framing it as responsible progress.

Yet independent analysts see something else. They note how past eugenics hid behind health claims, and how that line between therapy and upgrade blurs easily. With investments from figures like Altman and Armstrong, totaling millions, it looks like bets on breakthroughs in lax jurisdictions. Communities tracking this argue enforcement fails across borders, leaving private clinics unchecked and long-term risks ignored.

Faith perspectives cut deeper. For them, editing germline DNA isn’t just science—it’s tampering with creation, reminiscent of Noah’s corrupted era. Official talk of precaution doesn’t address these spiritual stakes or the inequality that could arise from elite access to edited offspring.

Standing at the Threshold: What It All Might Mean

Here’s what stands firm: Preventive is real, backed by $30 million from Sam Altman, Brian Armstrong, and others, targeting embryo edits for disease prevention. Most countries ban heritable applications. History warns us—US sterilizations, Nazi programs—showing how “improvement” science can turn dark.

Uncertainties linger: Where will implants happen? What private talks guide this? Gene editing tech works now, but governance lags, risks span generations, and questions of human identity loom. For prophecy watchers, it echoes Noah’s days of fleshly corruption and judgment. Others see technocratic divides widening.

We face a pivot. Is this easing suffering, or engineering a new human line with unseen fallout in body, society, and soul? The patterns suggest watching closely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Preventive is a startup that focuses on editing human embryos to prevent hereditary diseases. It has raised about $30 million from investors like Sam Altman and Brian Armstrong. While it claims to target medical issues, critics see broader implications for trait selection.

Observers point to historical eugenics, like US sterilization laws affecting 60,000 people and Nazi programs sterilizing over 400,000, which started as health initiatives. They argue embryo editing could slip into designer traits, echoing those coercive patterns. The concern is market forces normalizing a new standard for “acceptable” children.

Faith-based commentators reference Genesis 6 and Matthew 24, seeing gene editing as akin to the “corruption of flesh” in Noah’s time that led to judgment. They view it as a potential end-times sign, where human boundaries are crossed. This resonates with patterns of elite-driven genetic changes.

It’s prohibited in at least 75 of 96 surveyed countries, including the US and UK for reproductive use. Some allow limited research, but none permit open-ended pregnancies with edited embryos. This drives speculation about offshore jurisdictions with weaker regulations.

Groups like the WHO emphasize precaution, calling for more debate before reproductive use. They distinguish between therapeutic edits for diseases and enhancements. Critics say this ignores historical slippages and cross-border enforcement challenges.